Wisconsin is layered by time.

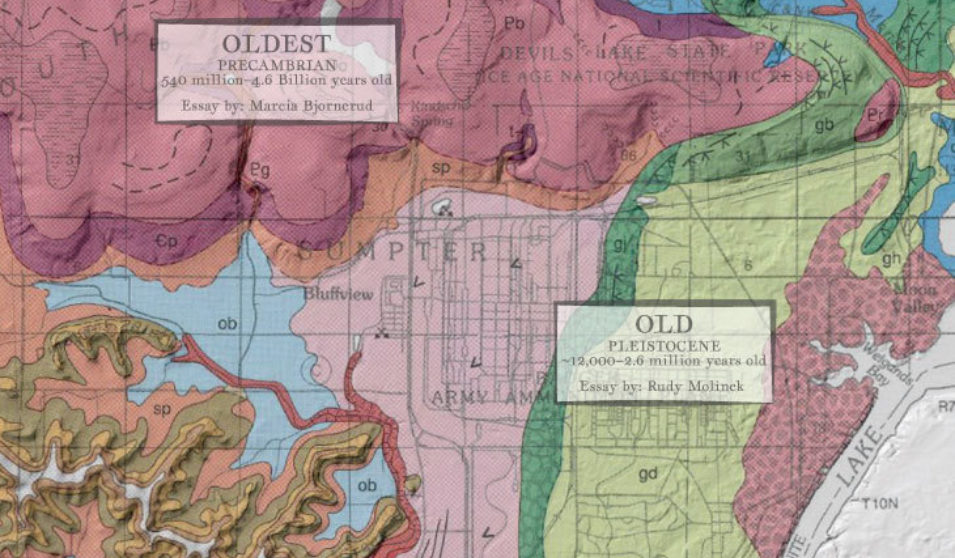

Three main geological periods present themselves across the state. Old: Glaciers moved across the land repeatedly through the Pleistocene, beginning their great last melt-back just twenty-one thousand years ago. Geologists noting the prominent glacial marks named that last episode of continental ice expansion the Wisconsin glaciation. Older: They also named an exception to the rule of glaciers. Southwest Wisconsin, unburdened by ice and its residues of sand, gravel, and boulders, is the heart of the Driftless Area. Paleozoic sandstones, limestones, and shales laid down under ancient seas 250 to 550 million years, are exposed in the Driftless, and underlie much of Wisconsin from Eau Claire to Kenosha, La Crosse to Green Bay. Oldest: Billion-plus-year-old basement rocks of the Precambrian, hard and dense and resistant, extend down from Canada, cover the northern third of the state, and surface in a few outlier outcrops.

Seemingly solid, Wisconsin rocks flow through time. They well up from deep Earth furnaces. They boil and harden, crust over, melt again, re-form and fold themselves over. They break and crumble down to bits, drift in sea waves, deposit themselves flat and even, compress and surface, erode again, flake away under the force of moving waters. Ice plows them over, transports them, tumbles them over and over into smooth round cobbles, leaves them high and dry on ridgetops, drops them down into kettle bowls. We explore here one spot, in Sauk County, where the state’s layers meet and the three voices of geology sing—old soprano, older tenor, and oldest bass—and keep time together.